For many years, Kaizen has been mainly linked to industrial operations. However, limiting continuous improvement to these areas reduces its true potential.

This article explores the fifth paradox of a Kaizen Culture: the premise that continuous improvement extends well beyond operations. What started as a method for eliminating waste in production has evolved into a management system applicable to all areas of an organization, including commercial and administrative operations, product development, human resources, and finance.

Organizations discover new ways of working by applying Kaizen to all functions and sectors. This article explains why this change in mindset is essential and how it can improve organizational performance.

What is a paradox?

Originally, the word paradox referred to an idea that goes against common opinion, but once understood and applied, it reveals a deeper level of truth. This logic is precisely what defines the paradoxes of a Kaizen Culture.

In the context of continuous improvement, paradoxes are statements that may seem contradictory or even illogical at first. Still, they challenge traditional mindsets and unlock new ways of thinking, leading, and acting.

Understanding these paradoxes is essential for any organization aiming to evolve into a culture of sustainable excellence—one that can innovate, adapt, and improve every day, at every level.

The 7 paradoxes of a Kaizen Culture

Over decades of working with organizations around the world, the Kaizen Institute has identified seven core paradoxes that underpin the development of a true Kaizen Culture. These paradoxes help dismantle limiting beliefs and align behaviors with a continuous improvement philosophy focused on creating value.

Here are the 7 paradoxes of a Kaizen Culture:

- Practice over tools.

- Small is not the only Kaizen.

- Efficiency begins with flow.

- Standardize to improve.

- Kaizen is more than operations.

- Kaizen is a meta-strategy.

- Kaizen is the smartest way to run a business.

In this article, we explore the fifth paradox: “Kaizen is more than operations.”

This paradox challenges the belief that continuous improvement belongs solely to the world of production, showing how a Kaizen Culture can be applied across all areas of an organization and in every industry.

The traditional belief: Kaizen is only for production

For decades, Kaizen has been closely linked to the shop floor. Its roots in the Toyota Production System and its success in the automotive industry reinforced the idea that continuous improvement was synonymous with operational efficiency. It was seen as something for machine operators, process engineers, and industrial managers—focused on eliminating waste and increasing productivity.

This belief became a deeply ingrained mindset: Kaizen is for production, and the rest of the organization should use other approaches. However, this narrow view has real consequences—more visible today than ever before.

The limits of a narrow application

When Kaizen is applied only to operations, a major opportunity for organizational transformation is lost. The gains achieved in production don’t extend to other areas, and the full potential of continuous improvement remains confined.

Focusing improvement efforts solely on production and logistics may generate efficiencies, but often with limited impact on the customer experience. Operations might be running with excellence, while sales are disorganized, marketing is ineffective, or customer service is inconsistent.

Limiting Kaizen to the factory and operations leaves most of the organization without a structured response for improvement.

Resistance in non-operational areas

Applying Kaizen to functions like sales, marketing, product development, or human resources often meets resistance. These teams argue that their work is too creative, dynamic, or unpredictable to follow structured standards or improvement routines.

This resistance, however, stems from a misunderstanding of what Kaizen truly is. When viewed merely as a set of industrial tools, it may seem ill-suited. But when understood as a leadership system, a culture, and a set of habits that drive excellence, it becomes highly relevant—regardless of function or industry.

Functional silos and a fragmented culture

Keeping Kaizen restricted to operations reinforces organizational silos. It creates a dual culture: on one side, disciplined teams with structured improvement routines; on the other, areas without a clear framework, where progress is reactive and unsustainable.

This fragmentation blocks cross-functional collaboration, which is essential for solving complex problems and accelerating innovation. Even worse, it sends the message that only certain areas are responsible for improvement—leaving the rest of the organization on the sidelines of progress.

The traditional belief: Kaizen is only for production

For decades, Kaizen has been closely linked to the shop floor. Its roots in the Toyota Production System and its success in the automotive industry reinforced the idea that continuous improvement was synonymous with operational efficiency. It was seen as something for machine operators, process engineers, and industrial managers—focused on eliminating waste and increasing productivity.

This belief became a deeply ingrained mindset: Kaizen is for production, and the rest of the organization should use other approaches. However, this narrow view has real consequences—more visible today than ever before.

The limits of a narrow application

When Kaizen is applied only to operations, a major opportunity for organizational transformation is lost. The gains achieved in production don’t extend to other areas, and the full potential of continuous improvement remains confined.

Focusing improvement efforts solely on production and logistics may generate efficiencies, but often with limited impact on the customer experience. Operations might be running with excellence, while sales are disorganized, marketing is ineffective, or customer service is inconsistent.

Limiting Kaizen to the factory and operations leaves most of the organization without a structured response for improvement.

Resistance in non-operational areas

Applying Kaizen to functions like sales, marketing, product development, or human resources often meets resistance. These teams argue that their work is too creative, dynamic, or unpredictable to follow structured standards or improvement routines.

This resistance, however, stems from a misunderstanding of what Kaizen truly is. When viewed merely as a set of industrial tools, it may seem ill-suited. But when understood as a leadership system, a culture, and a set of habits that drive excellence, it becomes highly relevant—regardless of function or industry.

Functional silos and a fragmented culture

Keeping Kaizen restricted to operations reinforces organizational silos. It creates a dual culture: on one side, disciplined teams with structured improvement routines; on the other, areas without a clear framework, where progress is reactive and unsustainable.

This fragmentation blocks cross-functional collaboration, which is essential for solving complex problems and accelerating innovation. Even worse, it sends the message that only certain areas are responsible for improvement—leaving the rest of the organization on the sidelines of progress.

The new vision: Kaizen across all functions and sectors

The new vision of a Kaizen Culture challenges traditional boundaries and recognizes that continuous improvement is not exclusive to production. It’s an approach that can—and should—be applied across the entire organization. From marketing to innovation, from sales to human resources, from customer service to finance—every function and sector benefits by embracing a culture of continuous improvement.

This is the true significance of the fifth paradox: “Kaizen is more than operations.”

By moving past the narrow view of Kaizen as a set of shop floor tools, organizations unlock the path to more profound, cross-functional, and strategic cultural transformation.

Bring continuous improvement to every area of your organization

Adapting tools to each function’s reality

Expanding Kaizen doesn’t mean blindly applying the same production tools to other areas. It means using the core principles—such as focusing on customer value, eliminating waste, and solving problems in a structured way—while adapting the toolsets to fit the specific realities of each function.

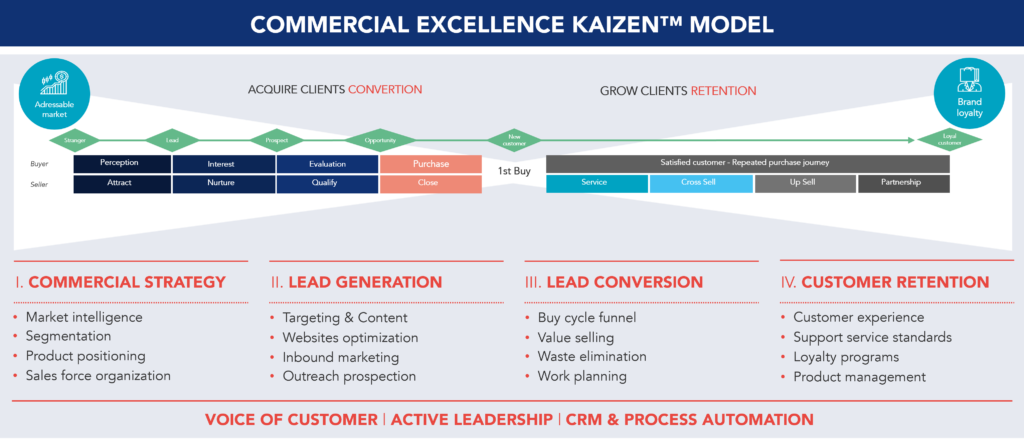

For example, in marketing and sales, there is a dedicated set of methodologies designed to improve the entire commercial process—from lead generation and qualification to conversion and customer retention.

Figure 1 – Example of a tool system for marketing and sales

In human resources and finance, there is a specific toolset designed to reduce lead times, increase process reliability, and improve the customer experience. These tools also include approaches for managing and developing talent.

In product development, dedicated methodologies support both portfolio and capacity management, as well as the optimization of the entire development cycle—from ideation to production launch.

The key lies in customizing the methods to meet each function’s needs, while staying anchored in the core principles that sustain a culture of continuous improvement.

Building a cross-functional improvement culture

When Kaizen is practiced across the organization—not limited to a single function—it gives rise to a cross-functional culture of improvement. Teams stop improving in isolation and start collaborating, breaking down silos and building truly integrated solutions.

This culture is rooted in hands-on, participative leadership, visual routines, daily meetings, and cross-functional projects that generate real impact on the organization’s core processes. In this environment, Kaizen becomes a common language—spoken by everyone contributing to the organization’s future.

How to apply Kaizen beyond operations

Applying Kaizen outside the operational context requires rethinking the approach to continuous improvement. It means engaging all functions of the organization—each with its own dynamics—and adapting methods to their unique challenges and goals. Below are five essential steps for applying this new vision.

Expanding the improvement mindset

The first step is to challenge teams to move beyond the narrow view that Kaizen only applies to industrial settings. Every area has flows, waste, problems, and improvement opportunities. Teams must be trained to recognize these elements and take ownership of their continuous improvement.

Customizing methods and systems

Each function has its own characteristics and needs. That’s why continuous improvement systems must be tailored to reflect each area’s reality, including its language, objectives, and challenges. It’s essential to invest time in developing function-specific methodologies that employees find helpful and valuable in their day-to-day work.

Promoting cross-functional teams

The most critical problems are rarely confined to a single function. Launching projects with cross-functional teams is essential for addressing complex challenges and improving the overall customer experience. This type of collaboration aligns priorities, encourages the exchange of perspectives, and leads to more robust, sustainable solutions.

Embedding continuous improvement into daily routines

Improvement becomes part of the culture only when it shifts from being an exception to becoming a routine. Daily meetings, visual task management, and structured problem-solving routines should be used across all areas. This builds momentum and increases team engagement in continuous improvement.

Measuring with customer-oriented indicators

Improvement efforts must be aligned with performance indicators focused on the customer. It’s essential to continuously monitor metrics that reflect value creation from the customer’s perspective—such as lead conversion rates, customer satisfaction levels, or the time required to develop new products.

What if your organization could improve every day? Find out how

Conclusion: Kaizen is a management system for all functions and all sectors

For decades, the Kaizen methodology was almost exclusively associated with industrial production. However, this framing is far too limited for the true potential of continuous improvement. What began as a philosophy rooted in the operational environment has evolved into a cross-functional management model—capable of transforming any area within an organization.

The fifth paradox of a Kaizen Culture directly challenges this narrow view. Continuous improvement doesn’t belong only to the factory floor—it belongs to everyone involved in creating value.

To unlock this potential, organizations must break away from outdated mindsets, tailor methodologies to fit each function’s reality, and engage the entire organization in a coordinated effort. In doing so, improvement becomes a shared language, a daily practice, and a driver of sustainable growth.

Kaizen is a way of thinking, leading, and collaborating—applicable to any sector and any team committed to being better today than yesterday.

Article based on the book The Kaizen Culture Paradox – The Smartest Way to Run a Business by Alberto Bastos and Euclides Coimbra (coming soon).

See more on People & Culture

Find out more about improving your organization